When you Google Digital Citizenship, the results are endless. The number of sites and resources dedicated to what it means to be responsible online are plenty. Two of my favourites happen to be ISTE’s Standards for Students and Common Sense Education.

These sites, among many others, offer a wealth of information on creating your digital footprint, privacy and security online, trustworthy sources for information, and communication and cyberbullying. What I found however, was that what I was looking for was a little too specific. I needed something to help me talk about the responsible use of technology BEFORE we’re living online; when what we’re using technology for lives on the device, not the internet.

I’ll take it back for a second.

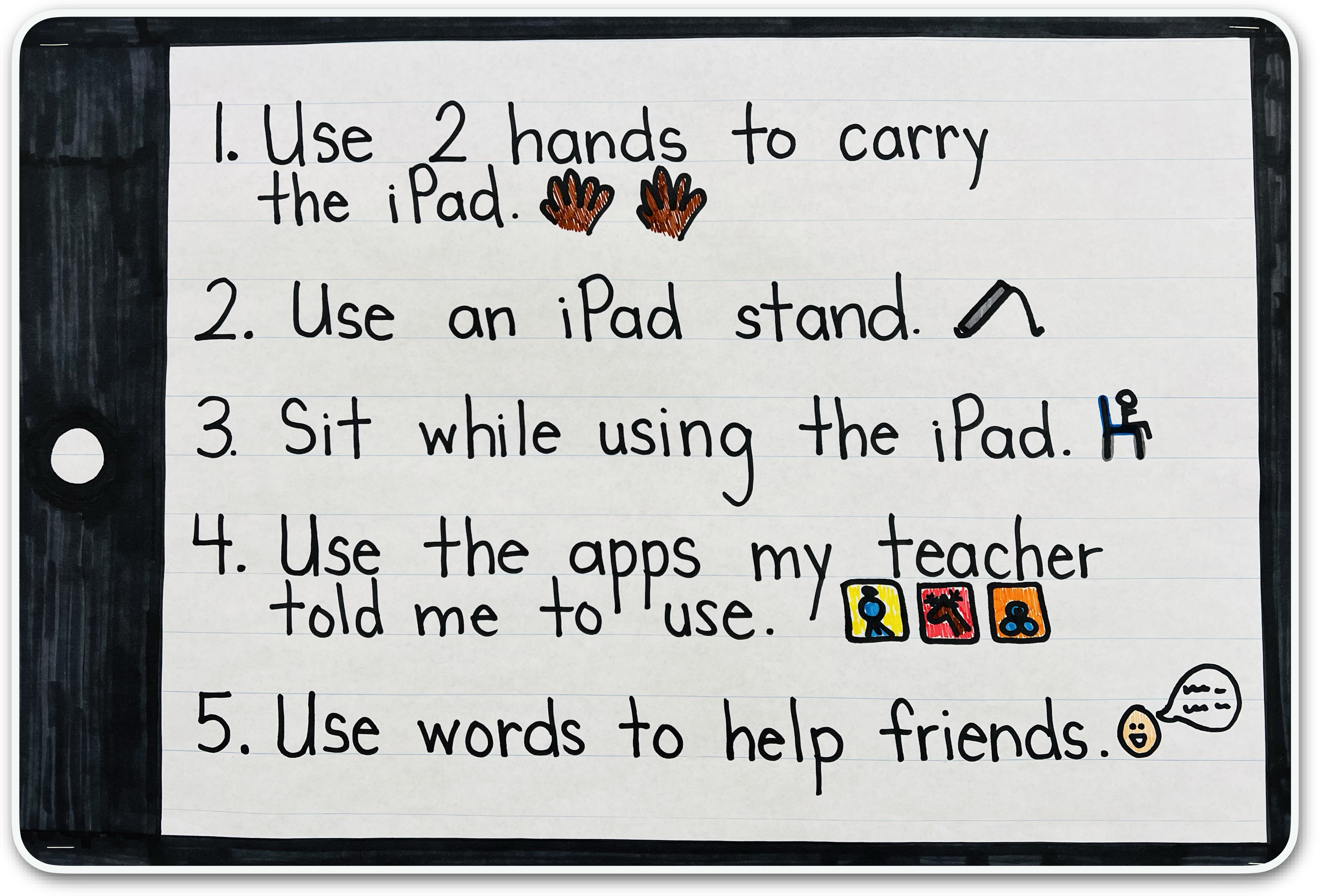

When I introduce technology to my K-2 students, the first piece we talk about is safety. How do you safely handle an iPad? How do treat the robots? Carry everything with two hands and use robots on the floor. Help your friends who ask for help and share the technology. Etc. etc.

When we start using our iPads for content creation, we inevitably have the conversation about taking photos. What photos are you allowed to take? What are you allowed to do with those photos? Etc. etc. In years past, this was all I needed. Most of the time any technology was being used, I was in the general vicinity. I assumed we were using the technology appropriately because it’s what we’d been taught. What this year has taught me is that the more likely reason was because I was standing ten feet away. Why? Because 5-, 6-, and 7-year-olds are 5-, 6-, and 7-year-olds.

This year has been a very different year. I’ve been able to release more control over our classroom, empowering my students to make the classroom theirs, not mine, to make choices that allow them to discover and create, and to take responsibility for their own learning. I’ve been able to do this, firstly, because I have a group of students who make this possible, secondly, because I have families who support my beliefs and pedagogy about what education should be, and finally, because I’ve done the research—both in books and in action. What this means is that on any given day there may be 20 different things happening at one time. When it comes to the technology, 10 iPads could be in ten different corners of the room. 10 robots could be travelling in 10 different directions. Any number of things can be happening, and though I’ve trained myself to be somewhat of an octopus, I am still only one adult, in one place.

I digress.

With this type of learning comes very high expectations for making the right choice. If you are using the technology, the expectation is that you are using it appropriately, responsibly, and respectfully. And not out of fear of getting into trouble, but because it’s the right thing to do. But that doesn’t happen magically. It happens through discussion, practice, and application. Then I found out that some undesirable choices were being made when I thought innocent Adobe Spark and Chatterpix videos were being created. Nothing that happened was of a serious nature by any means, but if left unaddressed, these actions can easily escalate as age and access grow.

Back to digital citizenship. Reactive me wanted to remove the technology. In fact, reactive me did exactly that. No technology, no problem. Reflective me knew that no problem meant no learning. I took to Google to find some information about how to address our issues more specifically. But I couldn’t find what I needed. Most of my research lead me to online behaviour. So, I did the next best thing – probably the first thing I should have done actually – I went to a colleague with experience with technology and digital citizenship. Much of what we do with our younger students and technology isn’t online and if it is, that piece is in our hands. They don’t have the capacity to understand the world wide web, and just how big it actually is.

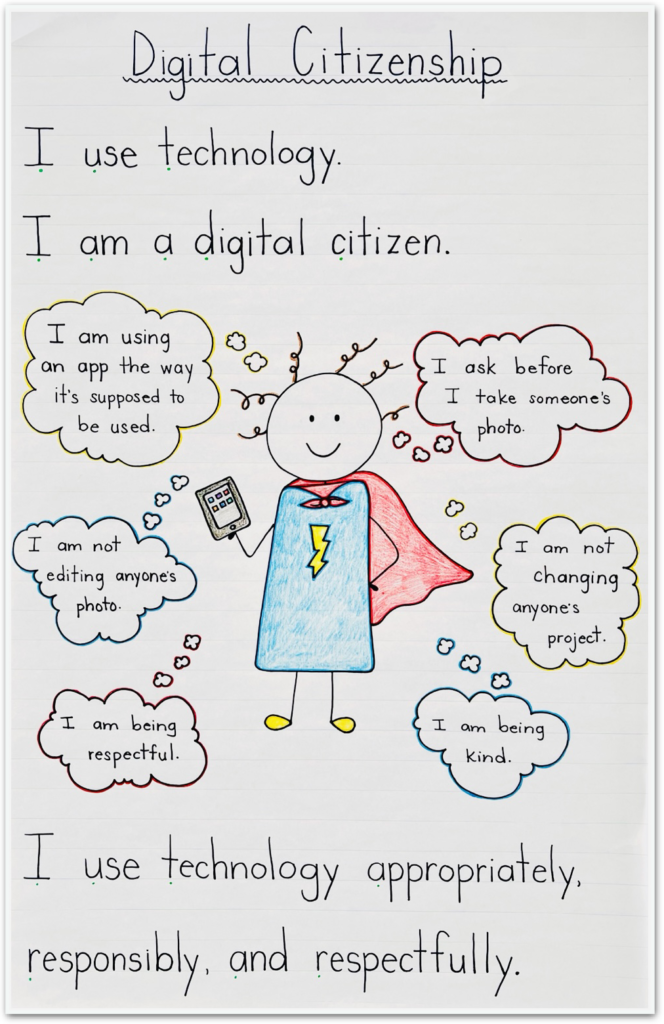

In the end, I picked up a marker, a piece of chart paper, and left it in the hands of the 19 people this needed to make sense to. I defined the term digital citizen as someone who uses technology to create, to communicate with others, and to find things out and they did the rest. I posed the questions: How do I use technology? How am I showing digital citizenship? And I listened to what they said. I learned what they knew, and what they didn’t. Turns out they knew that they shouldn’t take photos of others without asking, but most didn’t know why. They knew they shouldn’t change or edit photos or projects but couldn’t really explain why and temptation far outweighed anything else. As far as they were concerned it was because I said so. Ah. There it was. I was doing a great job of stating rules, but without meaning and relevance, rules are just words. I just assumed they knew.

And so, where did that leave us? It left me with a whole new appreciation of stated and implied rules and expectations with technology. It left them with a clear understanding of empathy and digital citizenship. And it left us with a brand new anchor chart that found a permanent home on the wall of our classroom. A daily reminder of doing the right thing with our technology.

There is so much more to digital citizenship than our online behaviour. We often graze this discussion because our youngest learners are rarely online without us close by and so maybe it feels like it doesn’t apply to them. The idea of the world wide web is too big for them to grasp and often for us to teach. But maybe it’s time to drop the adjective “digital”.

Citizenship in 2022 needs to refer to more than just online behaviour because it’s what exists BEFORE this stage that is so essential. It’s the conversation that needs to happen so when we’re off in the big wide world of the internet, we have something grounding us. It’s so when we’re surrounded by opportunity and temptation, we make the right choice. And not out of fear of consequence, but out of a duty to do the right thing.

Comments

One response to “Digital Citizenship in 2022”

[…] http://daphnemcmenemy.com/digital-citizenship-in-2022/ […]